In our beginning

Living on the Balla wiyn

In Wadawurrung language, the Bellarine Peninsula is known as Bella Wiyn, which means ‘recline on the elbow by the fire’ – resting place.

There were 25 known Clan Groups across Wadawurrung Country, connected through Cultural and shared interests, totems, trade, and marriage.

Swan Bay’s waters, intertidal flats and saltmarsh, as well as the woodlands in the catchment, would have been a rich source of food, ideal for hunting and gathering.

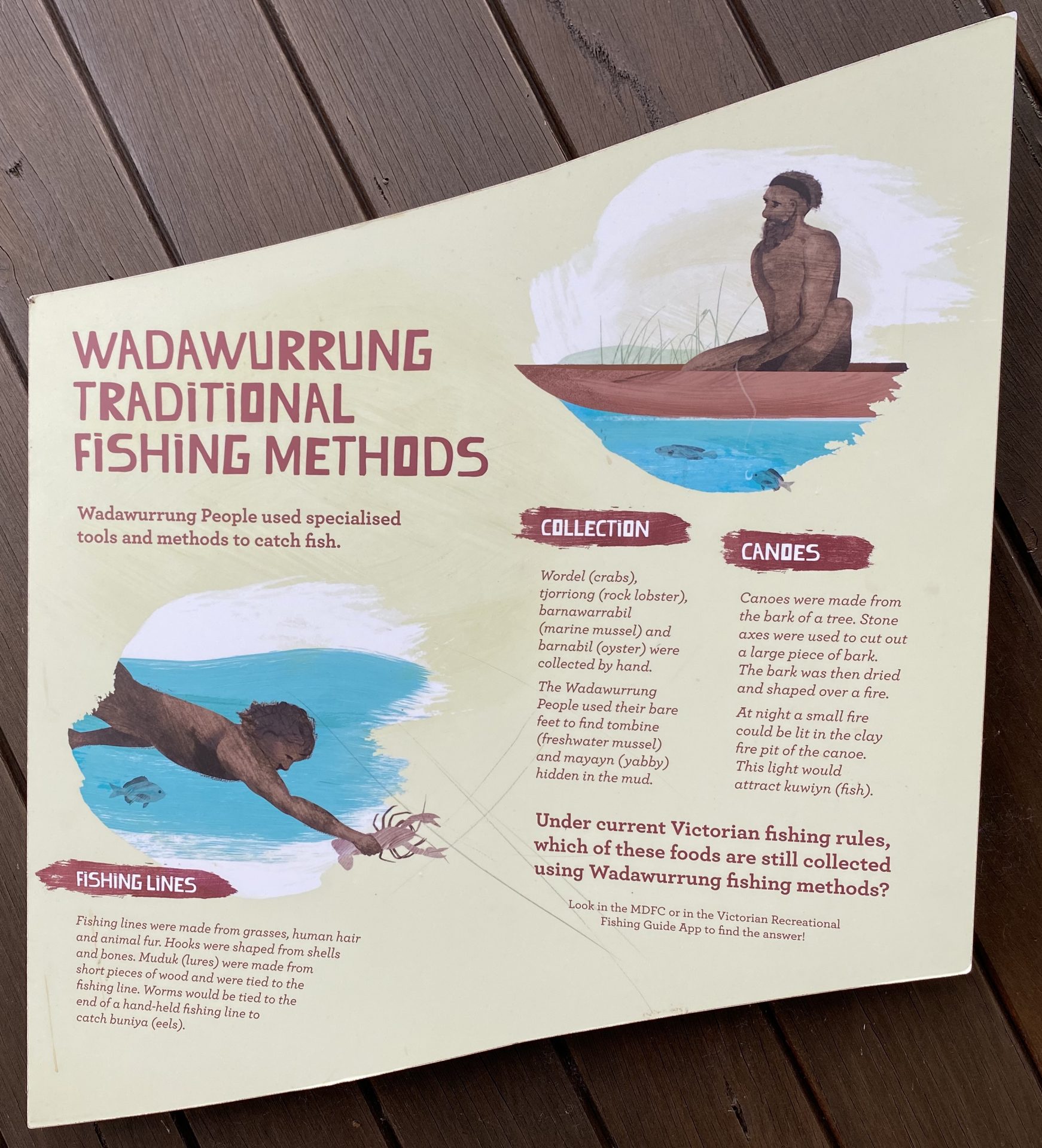

Fishing and hunting

Fish harvesting systems used by Wadawurrung people included fishing by hand to catch rock lobsters, marine and freshwater mussels and yabbies.

Fish traps made from flax, reeds and grasses were circular in shape. The fish and eels were caught when they entered the baskets at high tide and were unable to escape as the tide ebbed.

This sign is one of several about Wadawurrung Country at the Marine Discovery Centre in Queenscliff.

Spear fishing was another method used to catch mullet, blackfish, trout and bream, with the spears being made from blackwood or the roots of coastal trees, stone and reeds. One man stood in the water with the spear and a second man, stationed on higher ground, would call out the location of the fish.

Fishing nets made from bark, grasses and rice flowers were stretched across waterways and held in place by stones, branches, sticks and reeds. Fishing lines were made from fur, hair and grasses, with the lures made from wood and the hooks from shells.

Animals hunted on land by the Wadawurrung included kangaroo, echnida, possum, lizards and snakes. Large water bird species were hunted from the water.

Cultural knowledge ensured that species were not over harvested. Hunting of a species was restricted to ensure its survival.

Cooking food

Cultural Heritage sites are registered across the Bella wiyn. Many of these are middens, which are piles of shells and bones that have compacted after cooking and eating, and formed over long periods of time. The middens along the Coast are fast disappearing due to development, erosion, climate change, sea level rises and recreational activities by the public.

The day’s harvest would have been cooked on hot coals; food was often wrapped in leaves and placed in a pit with hot stones or eaten raw. Women were primarily the gatherers of vegetables, roots, herbs, fruits, nuts, eggs and honey.

Cultural Heritage sites are registered along the Swan Bay, it being a place of plenty of food, medicine and fibre resources.

Using plants

A variety of plants were used for food, medicines and hunting tools. Austral Grass-tree spikes were used as the base of spears. The leaves of the Spiny-headed Mat-rush were used as a fibre to weave baskets. Murnong (Yam Daisy) tubers were an energy-rich and staple food:

‘After leaving enough tubers to enable future pickings, the women promoted the next year’s harvest by tilling and aerating the soil with their digging sticks. The soil was fertilised by the ash caused by the technique called ‘firestick farming’ where controlled autumn (around April) fires were lit in a mosaic fashion. This highly sophisticated technique, carried out by Wathaurong men, not only produced the vast grasslands, which the Europeans thought occurred naturally, but also promoted the best conditions for native plants and game to thrive. Firestick farming also minimised the risk of the damaging summer wildfires that occur all too often today’. - www.djillong.net.au/traditions/tandops-stories/land-cultivation.html

A version of ‘Firestick Farming’, now referred to as Cultural Burning, is practiced by Wadawurrung people today.

Shelter

Six seasons, not four

Animals and plants respond to seasonal changes. In European calendars there are just four seasons, but in Wadawurrung calendars there were six. The coming of each season affected how people moved around the region, what they hunted and gathered and where they did it. The six seasons are described in Chapter 4 of the book, Geelong’s changing landscape: Ecology, development and conservation and in summary are:

- Early and mid-summer (November to January): Black Wattle flowers. Gathering of Clans. Migration to sea.

- Late summer (February and March): Moonah blossoms. Eel traps set. Managed burning.

- Autumn and early winter (April and May): Birds migrate north. Mushrooms harvested. Billabongs fill. Clans move inland.

- Deep winter (June to Mid-July): Rivers flood. Clans move into semi-permanent rock shelters. Use Bower Spinach grown on roofs for food.

- Early spring and Spring (Mid-July to August): Coast Beard-heath flowers. Clans catch waterbirds in wetlands. Women collect Murnong (Yam Daisy).

- Spring (September and October): Seaberry Saltbush flowers. Traps set for animals. Snakes and lizards active. Clans gather for festivals.

Contact

The first reported contact between the Wadawurrung and Europeans was after Lieutenant John Murray entered Port Phillip Bay on the Lady Nelson in February 1802. For the Wadawurrung, that began a long period of dispossession from their traditional lands. Sealers and whalers abducted women and spread smallpox and syphilis. Many people died in conflicts with European settlers.

The release of sheep and the expansion of pastoral leases removed access to traditional food and water supplies, severely impacting on Wadawurrung people to continue caring and resourcing their traditional foods and medicines. The sheep ate the leaves and tubers of the Murnong, a key staple of the Wadawurrung diet, and the grasses were replaced by sown pastures.

The estimated Wadawurrung population in the Geelong area in 1803 was 700. By 1842, a census at Bukar Baluk (Fyansford) reported the population had dropped to 118. Another census in 1853 showed that the extermination of Wadawurrung people in the Geelong area was almost complete with only 17 Geelong Wadawurrung surviving.

In 1885, Willem Baa Nip, the last Wadawurrung living in the Geelong district, dies. Although he was the last Wadawurrung living traditionally in the Geelong region at this time, there was another living descendant of the Wadawurrung, and today his descendants are acknowledged as the Registered Aboriginal Party under the Cultural Heritage Act 2006.

Foster Fyans was appointed the Crown Lands Commissioner for the Portland Bay District in 1840 and wrote to Charles La Trobe that ‘the only plan to bring them [the district’s Aboriginal people] to a fit and proper state was to insist on the gentlemen in the country to protect their property, and to deal with such useless savages on the spot’. Papers relative to the massacre of Australian aborigines. House of Commons, London. 1839. pp.158, 159 https://archive.org/details/MassacreOfAustralianAborigines

George Adman wrote in his diary (held at the Queenscliffe Historical Museum) that in 1853 he recalled seeing, as a young fellow, Wadawurrung people going to Shortlands Bluff lighthouse for rations of food and clothing because the traditional food sources were gone or access was denied.

Ongoing connections to Country

Land and Water Management

- Land and Sea management team

- Cultural Values Management

- Co-management

- Acquisition

- Cultural Burning

- Representation on planning committeees

Us supporting us

- Culture and language strengthening Program

- Keeping Place - Safe place for people and artefacts

- Cultural Centre - Sharing and education - Enterprise

Strengthening Wadawurrung Corporation

- Employment and mentoring

- Enterprise development & support

- Recognition and respect of Wadawurrung people

- Partnerships and stakeholder engagement

- Structural reform

- Engage WAC members

SBEA would like to acknowledge Traditional Owners of Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation have reviewed this document (www.wadawurrung.org.au).